A packed room of politicos, lawyers, election directors, and legislators erupted in cheers and jeers when the idea of hand-marked paper ballots surfaced. In a fractious hearing of Georgia’s Blue Ribbon Election Committee, the only consensus lay in the depth of polarization over the embattled State Election Board.

The Aug. 28 hearing at North Georgia Technical College in Clarkesville laid bare a body consumed by internal feuds, legal missteps, and partisan suspicion. What should have been a sober review of election procedures became a study in dysfunction. Members sparred openly, questioned each other’s motives, and accused one another of eroding public trust.

At its core, the meeting forced lawmakers to confront a question few seemed ready to answer: Does the State Election Board (SEB) deserve more authority — or does it deserve to exist at all?

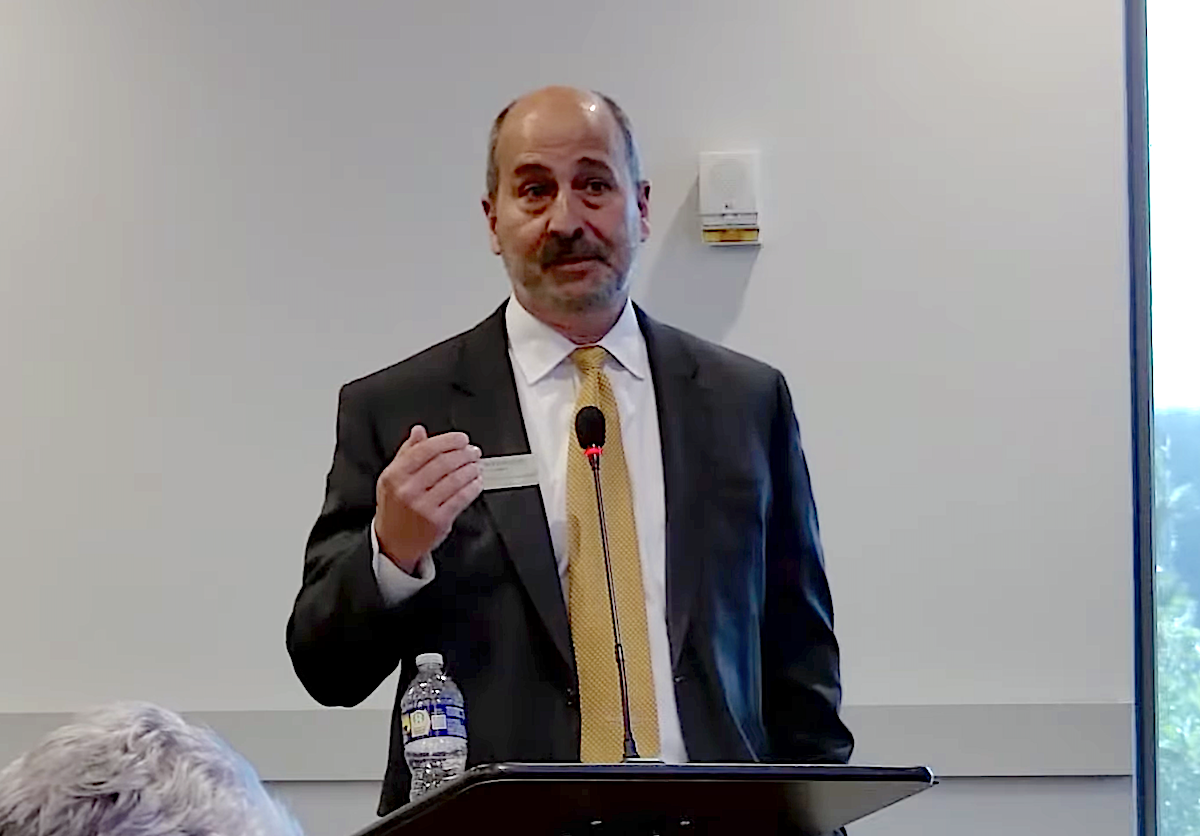

A chairman under fire

John Fervier, the board’s embattled Republican chairman, tried to frame the discussion with a clear explanation of the SEB’s statutory duties. Too many lawmakers, he warned, had never read the code they charged him to enforce.

He recounted the chaotic rulemaking of the past year: in fall 2024, the board proposed seven new rules on election procedures. The Georgia Supreme Court later invalidated four, upheld one — requiring video surveillance — and sent two back for further review. For now, only that surveillance rule stands.

Fervier also urged restraint, suggesting that if they keep creating new rules, they will drown in them. Fervier argued that the board could never clear its backlog of more than 100 unresolved cases if it “got bogged down” in a flood of new rules, and that tackling fraud complaints required focus, not additional regulation.

His message landed unevenly. Some Republicans on the panel pressed him on why investigators had not moved faster, and why the board employed only two investigators statewide.

Fervier countered that the problem was not a lack of manpower, but rather a lack of tools. Until recently, investigators lacked even government email addresses, conducting state business through Gmail accounts. Fervier explained that hiring more investigators would do little good if they remained unequipped, noting that they had only just received official government email accounts after relying on Gmail.

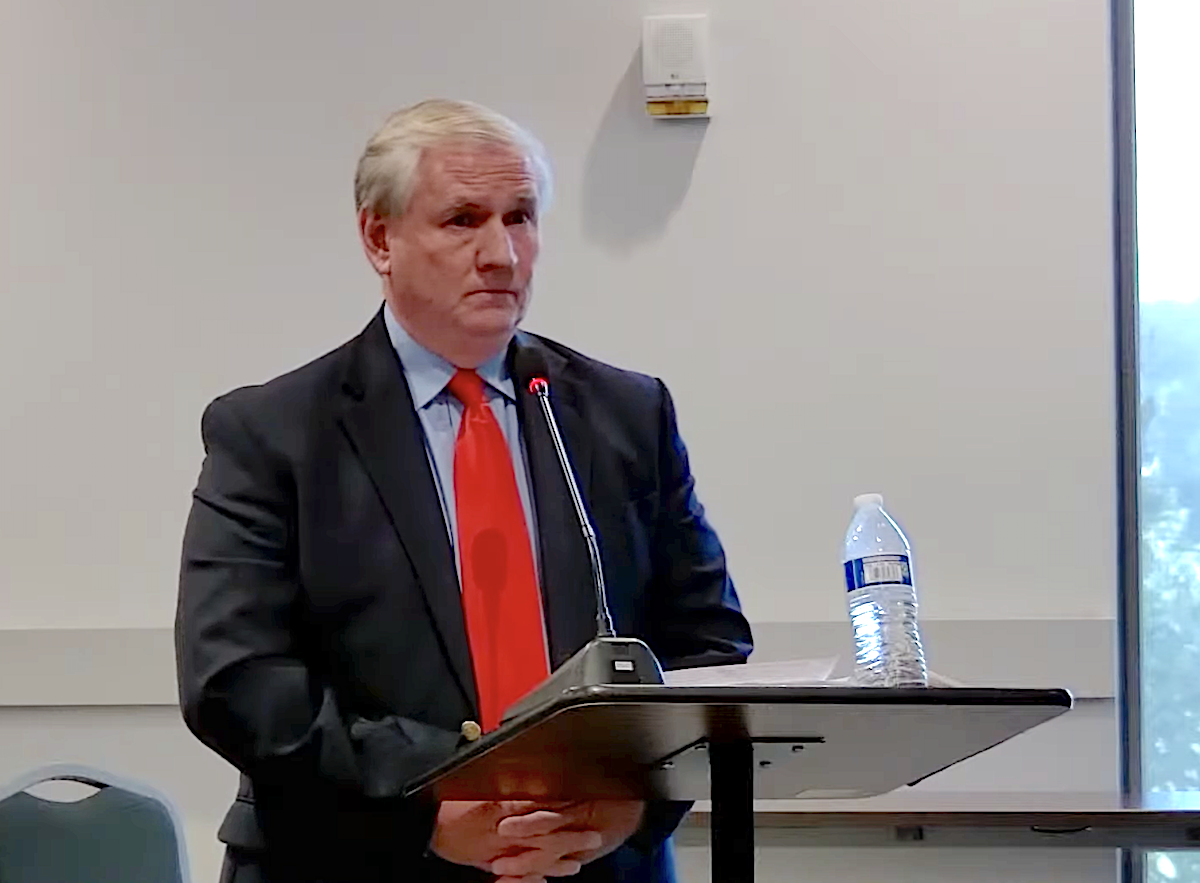

The Republican push

State Senate Majority Leader Steve Gooch (R-Dahlonega) underscored Republican priorities: hand-marked ballots and codified election rules. He countered concerns over the cost of paper ballots by floating an $80 million estimate for updating Dominion machines. The message drew cheers from the gallery.

Rep. Martin Momtahan (R-Dallas) pressed harder. Why, he asked, did criminal fraud cases even land at the SEB? “Why not send them straight to prosecutors?” he said, ostensibly suggesting the board was ill-equipped to act as a law enforcement body.

Other Republicans suggested codifying the SEB’s authority in statute, transforming it from a regulatory panel into what one Democratic leader later called “a new power center.”

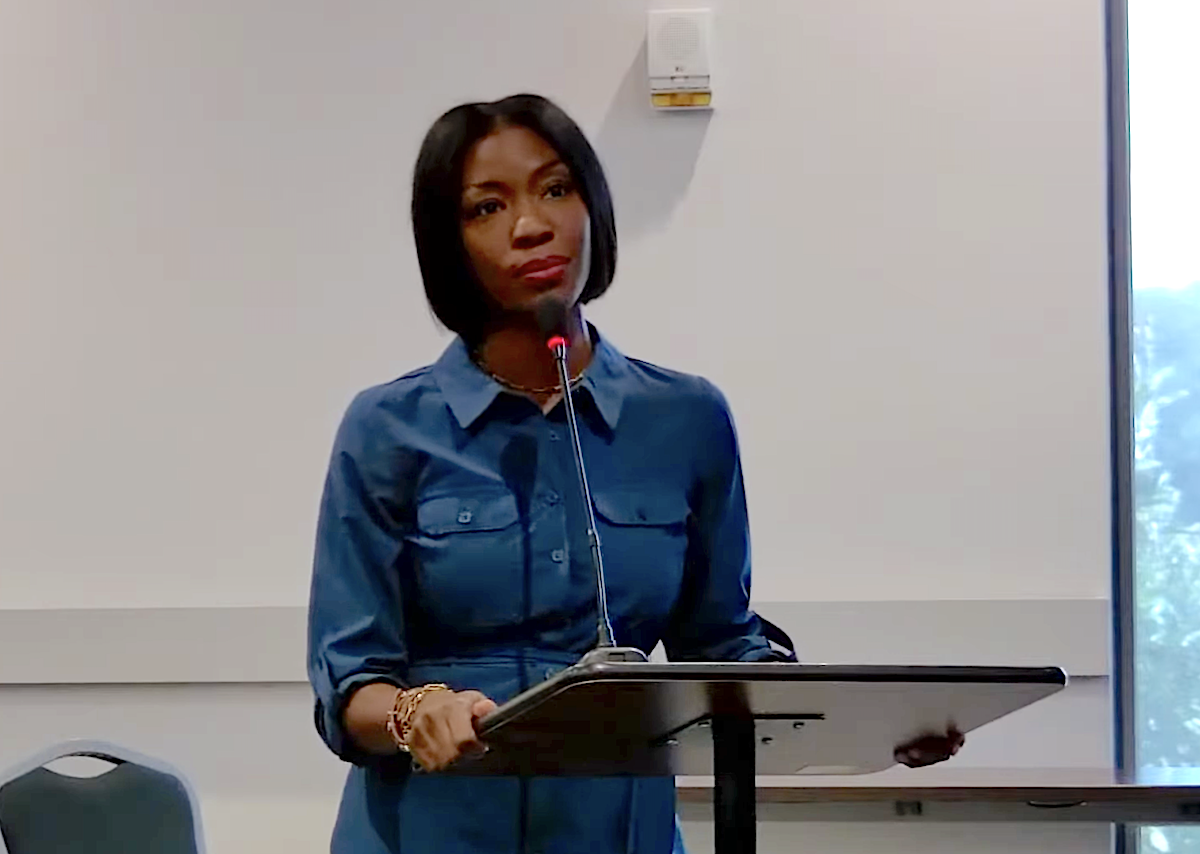

A Democrat’s rebuke

Democrat Sara Tindall Ghazal, the lone Democratic

appointee on the SEB, struck a different tone. She described her work as methodical and deliberately nonpartisan. “I try not to look at partisanship because I think that’s a disservice,” she said. “I take every case at face value.”

Ghazal outlined her decision-making framework: start with the law, then examine whether voters or counties face confusion. She warned that sudden rule changes, particularly those affecting certification, could create chaos. “That could mean some voters’ ballots count and others do not,” she said. “That is not acceptable.”

Her prescription for trust was simple: “Do the job. Keep moving forward. Be transparent.”

A matter of trust

While Fervier embodied the SEB’s institutional strain, and Ghazal its voice of restraint, a divide over conflicts of interest and trust produced the fiercest clash of the day. Blue Ribbon Study Committee member Rep. Saira Draper (D-Atlanta) and Republican SEB member Janelle King engaged in a sharp exchange.

The tension began when Draper raised what she called an unavoidable optics problem: King serves on the State Elections Board while her husband campaigns for political office. “If citizens of Georgia don’t know whether you are acting as a board member or as the spouse of a candidate,” Draper said, “that presents a trust issue.”

King bristled. “That’s your conflict of interest,” she shot back. She argued that unless her husband won the office of Secretary of State, no conflict existed.

Draper countered that trust, not legality, was the issue. “Trust is the most important thing,” she said.

King insisted she could support her husband and maintain integrity. She accused Draper of manufacturing a partisan narrative. “It benefits the Democratic Party for you to create this narrative,” King said. “But I have spoken with attorneys, I have looked at the code, and there is nothing wrong with what I’m doing.”

The exchange grew sharper. Draper pressed whether King would recuse herself if a conflict arose. King said she would. Draper expressed that Georgians had only her word. King assured the room she could be trusted. Draper answered flatly: “There is an appearance of impropriety.” King dismissed it: “In your head.”

Claims of dysfunction and dishonesty

If Draper’s first clash tested optics, her second cut to the board’s core dysfunction.

James Mills, the SEB’s executive director, opened with prayerful language about equality at the ballot box and at the ground by the foot of the cross. Then, to audible gasps, he turned fire and brimstone on his colleague Fervier. “I have never worked for a more dysfunctional, dishonest chairman than John Fervier,” Mills declared. Audience members clapped before he cut them off: “Please don’t clap. I don’t want claps. That should grieve our hearts. And it grieves mine to say that, and I only say that to this committee because you deserve to know. You deserve to know.”

Mills cited a recent board meeting when, after the SEB passed a measure, Fervier said he would “take it under consideration.” Mills called it “dysfunctional” and “dishonest” for a board chair not to uphold committee votes.

Appointed SEB chairman by Gov. Brian Kemp, Fervier has sought to strike a balance between his more moderate and far-right colleagues on the board. Last year, he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “Our job is to clarify law, not create new law,” adding, “This doesn’t need to be an activist board. This board needs to stay within its boundaries.”

Mills denied this is a “personality clash” and said he will continue to work with Chairman Fervier. However, Draper could not let the remark pass unchallenged.

“You know, I felt during your presentation that I was at home managing fights between my kids,” she told Mills. “This finger-pointing and naming names falls far beneath the respectability of this process. If you tell us the board is dysfunctional, at what point are you part of the problem?”

Draper then pressed Mills on a point of principle. Mills has argued that voters who commit fraud should pay court costs. Draper posed a parallel: if SEB members reject legal counsel and their actions draw lawsuits, should taxpayers foot the bill? Shouldn’t the board itself be held responsible?

Mills deflected, covering his face and shifting topics. Draper asked again. He refused again. “So what I’m hearing is you don’t want to answer my question,” she said.

The county view

While the board’s members sparred over rules and personalities, local election directors zeroed in on the mechanics of voting itself. Over lunch, Glenda Ferguson, director of elections in Dawson County, joined her counterparts from Union and Towns Counties to weigh the push for hand counts.

All three voiced skepticism. Hand counting, they argued, would slow results to a crawl, invite human error, and require armies of temporary staff. “Even when voters hand-mark their ballots, the ballots are still read by machine,” one of them said, noting that the system already provides a paper trail without the inefficiencies of a full manual count.

Their caution echoed the studies and remarks Fervier had cited earlier: machine tabulators make fewer errors than human tallies. Whether voters use electronic ballot-marking machines or mark pre-printed ballots by hand, the process still produces a paper ballot read by scanners, meaning the safeguard already exists without the delays and vulnerabilities of a wholesale hand count.

Dysfunction on display

The day’s testimony crystallized a bleak picture. The SEB has only two investigators for the entire state. Its website routes complaints through the Secretary of State, leaving board members uncertain whether they see every case. Investigators only recently acquired government email addresses. And, as Fervier reminded lawmakers, the board faces numerous backlogged cases.

The dysfunction has already cost Georgia. In fall 2024, when the board rejected legal counsel’s advice, lawsuits followed. The courts tossed nearly every new rule the SEB attempted. Taxpayers absorbed the cost.

At one point in the proceedings, Rep. Draper said, “There are so many agencies and committees across Georgia that don’t touch this level of dysfunction.”

Public trust on the line

Perhaps the sharpest rebuke of the day came from Elizabeth Reed, a political analyst, lobbyist, and now consultant, who warned that Republicans undermine themselves when they amplify conspiracy theories without proof.

“I’d advise against the sort of Nancy Grace approach where we make wild accusations and see what sticks — that’s only hurting the public trust in the elections process,” she said.

Reed pointed to Georgia’s 2020 Senate runoffs as an example: “I truly believe we have two Democrat U.S. senators right now as a direct result of Trump’s trickle-down Republican attacks on election integrity. Voters were essentially told, ‘The elections are rigged, so why bother?’ Republican turnout in the runoff that year was embarrassingly low.”

Her argument found an echo in real time from a trio of women sitting near the front row of the chamber, one of whom was a poll worker. They expressed disapproval whenever the rhetoric turned sharp, especially when James Mills disparaged Chairman Fervier, even gasping in shock at the nature of the allegation.

Reed and many who work the elections framed the same warning: trust in elections breaks not only when systems fail, but when leaders model dysfunction. Reed called for Republican candidates to present documented evidence and practical solutions if they allege problems, and to remember that sometimes, “you lose.”

The women in the gallery, through muttered commentary and headshakes, made the same point in plainer terms: the tone and behavior on display did little to restore confidence in Georgia’s elections.

The larger stakes

For Republicans, the path forward lies in giving the SEB more teeth: more investigators, more rules, more codified power. For Democrats, the board itself may be the problem. One suggested dissolving it altogether.

The prudence of a middle ground hung over the hearing. Could lawmakers streamline the SEB’s role, clarify its rules, and shield it from partisanship? Or had the dysfunction already hollowed it out beyond repair?

As one politico remarked after the meeting: What is the value of a watchdog that cannot stop fighting with itself?