If all goes according to plan, I will be standing somewhere in Yellowstone National Park or the adjacent Beartooth Wilderness as you are reading this article.

As an avid outdoorsman, Yellowstone has been very high on my list of National Parks I want to visit. The untold beauty of the area is unmatched anywhere else in the world, with arguably the best geothermal features in the entire world. From geysers, to beautiful springs, to just cool rocks the park is one non-stop geologic wonder.

The “Supervolcano”

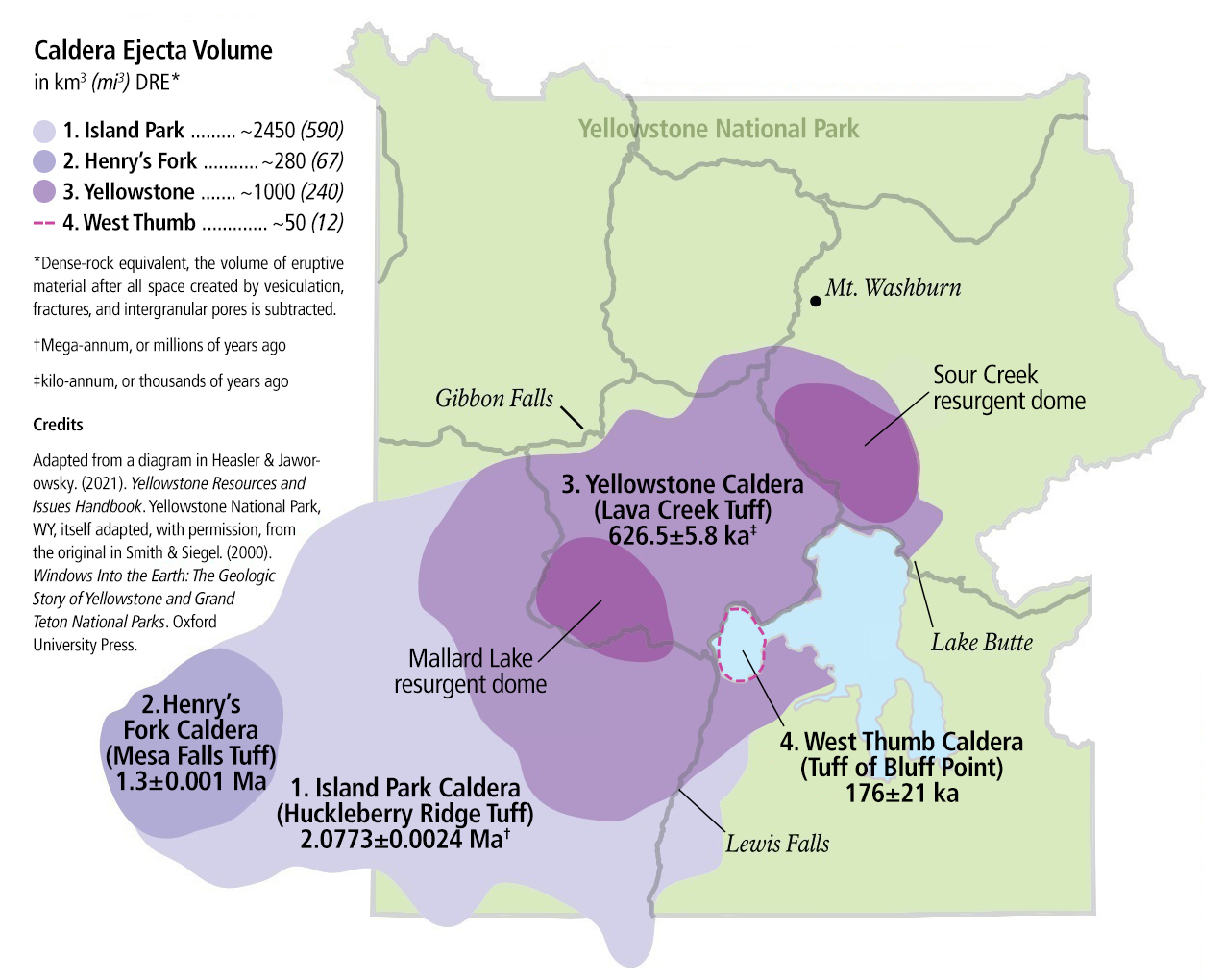

There are two different ideas of the Yellowstone “supervolcano”: the pop culture version, and the realistic one. The Yellowstone Caldera is a very large area that is roughly 17,000 square miles. This caldera isn’t just one giant volcano, but rather the remnants of several large, separate eruptions over the past couple million years. In the grand scheme of the Earth, the volcano is very young with the oldest volcanic rock in the area only 2.5 million years old. There have been 4 known eruptions roughly 2.1 million, 1.3 million, 626 thousand and 176 thousand years ago respectively.

This is all due to a “hot spot” that lies just beneath the surface. This area of magma close to the surface The Yellowstone Hotspot has been known to produce volcanos for at least 16 million years, and traces a path from eastern Washington up through Idaho and to it’s current spot under Yellowstone National Park. A hot spot is a place beneath the surface where magma is particularly close and is regularly replenished from below. The Hawaiian Islands were produced in this same manner.

While you may read that the Yellowstone “supervolcano” is overdue for an eruption, that couldn’t be further from the truth. With only 4 known eruptions in the past 2 million years, one anytime soon seems unlikely. Scientists are constantly monitoring the area for seismic and geothermal activity.

The Springs

Arguably the most iconic part of any National Park in the US is the Grand Prismatic Spring. Water filters down through the soil until it comes into contact with heated rock, around 6,000 feet below the surface. There it heats up to a boil and rises back towards the surface. When it gets there, it forms some brilliant pools of deep blue water. None are as impressive as the Grand Prismatic Spring. The bright colors are due to different types of algae that thrive in high temperatures, known as thermophiles. They have to love the heat, because the spring stays constantly around 160ºF. Since different bacteria thrive at different temperatures, the colorful rings work outward as the temp drops.

There are nearly countless pools and springs located throughout Yellowstone and new ones are forming regularly. In fact, one new hot spring was recently discovered by scientists on a routine check of the Norris Geyser Basin.

This slow movement upwards of water can also result in some very cool formations like the one below. When the water gets mixed with mud (generally limestone based), it creates a “mud volcano” that build beautiful, alien looking terraces.

Photo by Hana Oliver on Unsplash

In rare circumstances the water can be forced up a bit more channeled.

The Geysers

Geysers form under very, very specific circumstances and only exist in a few places in the world. Yellowstone National Park contains over 500 (perhaps as many as 1,000+), which accounts for over half the known ones in the world. Like springs and pools, water must filter down and touch hot rock, but in this case it is channeled up through a narrow escape route and experiences some sort of blockage. The result: a large surface explosion of hot water and steam when the pressure gets too great. By far and away the most well known geyser in the world is Old Faithful. It comes by its name honestly, erupting regularly every 1-2 hours (on average 90 minutes). According to the National Park Service, water from this geyser shoots as high as 150ft in the air and is a scalding 169ºF upon it’s exit. In addition, 3700 to 8400 gallons of water are expelled each eruption. Pretty cool if you ask me.

I am incredibly excited to witness these sights for myself, and you can look for tons of photos of not only the geothermal features, but also the abundant wildlife and wildflowers of the region. I will also be spending time on the Beartooth Highway and Beartooth Plateau hiking the high elevations where there is still snow.

I’ll see you on the road…..