Clarke County Sheriff John Q. Williams began Monday’s press conference with a somber acknowledgment: Three people have died in custody at the Athens-Clarke County Jail this year. A fourth death remains under investigation.

“Any death is unquestionably a tragedy, and the only number that we strive for is zero deaths of incarcerated people,” Williams said.

The confirmed in-custody deaths include Torrance Bernard Bishop, who died April 22; Shabazz Sangria Wingfield, who died May 5; and Boycie Tyrell Howard, who died July 9. A fourth man, Brent Monroe Boling, was hospitalized in critical condition after a medical emergency at the jail. He was released from custody on July 10 so his family could make end-of-life decisions.

“These are unimaginable tragedies, and my heart breaks for each and every one of you who have any connection to these individuals at all,” Sheriff Williams said. “They were members of our community and their lives mattered.”

Williams said the Georgia Bureau of Investigation is handling independent investigations into all four cases. He also ordered an internal review of jail policies and procedures.

Fentanyl threat

While the official causes of death have not yet been released, Williams said fentanyl is suspected in at least two of the confirmed deaths—and possibly more. The powerful opioid is at the center of what the sheriff called a growing national crisis now reaching the walls of Athens’ local jail.

“This isn’t just a distant story on the news,” he said. “It’s a stark, painful reality that touches our communities, our families, and the very incarcerated people that we house here.”

On July 8, the same day Howard was found unresponsive in his cell, two other inmates were hospitalized following suspected drug overdoses.

Jail officials believe the most recent batch of fentanyl was smuggled in by a newly arrested individual and distributed to others. There is no evidence, they said, that any jail staff were involved.

Williams described fentanyl as a threat unlike any the jail has faced before. Its potency and concealability make it difficult to detect, even with body scanners and searches. He emphasized that even small amounts, no larger than the tip of a pencil, can be fatal.

“We have to understand that we’re never going to be able to 100% eliminate contraband from entering the jail, especially something in the form of fentanyl,” the Sheriff said. “People can smuggle it in in a belly button, in between your fingers. People are very creative when it comes to these things.”

Stemming the flow of contraband

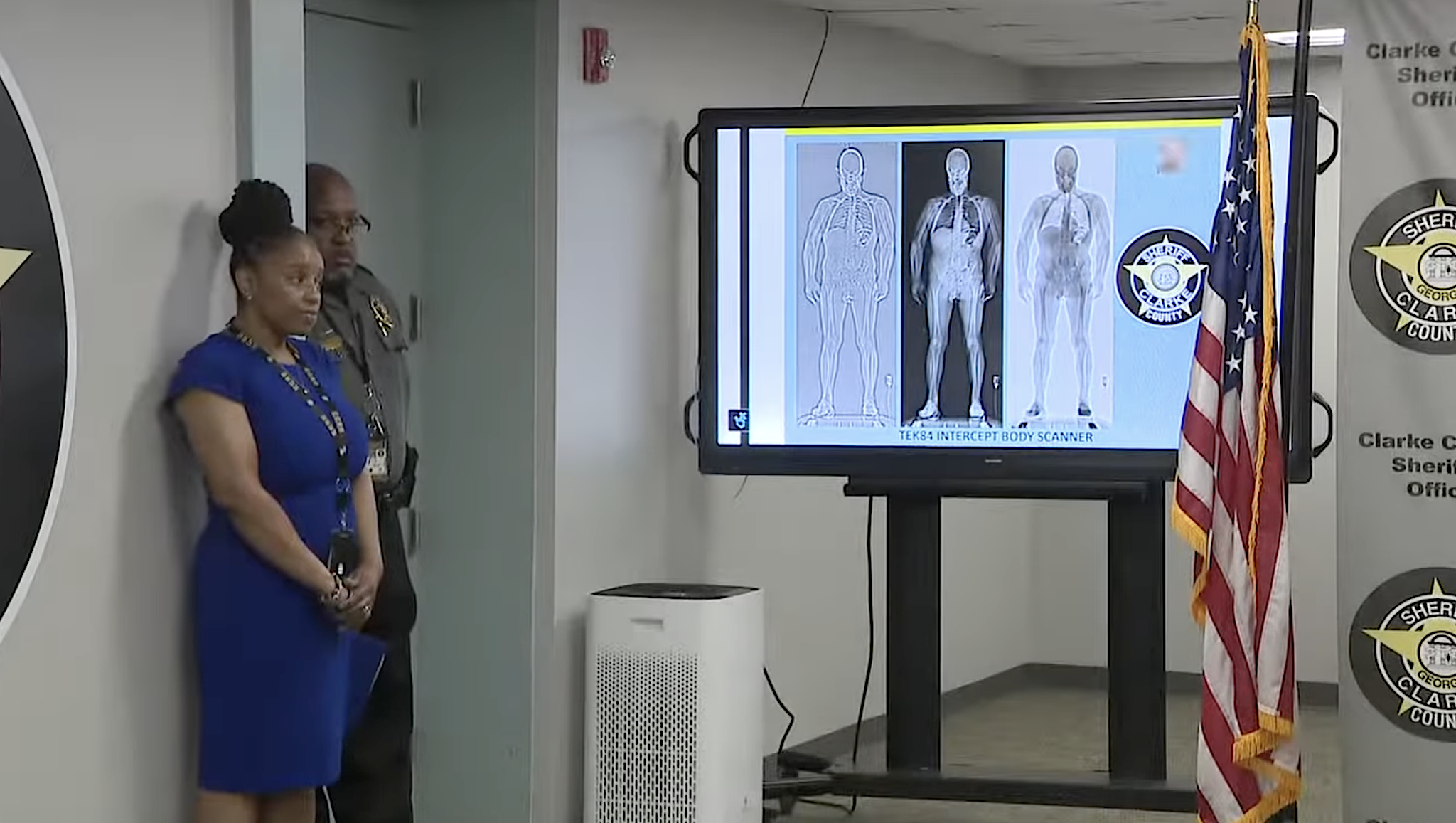

Jail leadership outlined steps they’re taking to fight the problem, including increased use of body scanners, overdose drills, and universal access to Narcan. However, Chief Deputy Frank Woods said the jail is short more than 40 employees, with some shifts running at half strength. He also noted the facility’s outdated security system and limited camera coverage.

“Budget requests for funds to replace the system have been submitted numerous times and will be again this year,” said Woods. He added, “When we’re fully staffed, we’ll be able to increase supervision and observation, which will, we believe, greatly reduce the likelihood of substance use within our facility.”

Woods said, for now, jail administrators will continue to focus on training staff to prevent the flow of contraband throughout the facility. They’re posting warnings in housing units about the dangers of accepting unknown substances, similar to those seen in airports. The sheriff’s office is also working with the district attorney to pursue charges in cases where contraband is discovered.

Beyond enforcement, the focus remains on recovery and rehabilitation. The jail’s re-entry and recovery programs aim to give individuals the tools they need to rebuild their lives.

Recovery assistance

Captain Tony Howard and healthcare director Andrew Smalls shared how the jail screens individuals during intake, evaluates medical needs, and connects them to addiction treatment. The jail partners with MEDIKO to provide mental health and substance abuse services, including medication-assisted treatment, AA/NA, relapse prevention, and reentry planning.

Since 2024, more than 1,000 residents have participated in recovery programs. Yet many challenges remain, particularly in the area of mental health, jail officials said. Two of the men who died had been court-ordered into inpatient psychiatric treatment but were still waiting for placement in state hospitals—one for nearly 300 days.

Woods said the Athens-Clarke County Commission “gave us the money to have the resources that we have, but it’s not what a hospital has.”

Williams echoed the call for more resources, education, and collaboration. He urged community members, commissioners, and state lawmakers to visit the jail, learn about its challenges, and support efforts to improve conditions. And he stood by his department’s focus on rehabilitation: “Sometimes people just need this little thing called hope.”